Traveling the Silk Road

“To transmit and spread the teachings of the Lotus Sutra no doubt required the efforts of bodhisattvas of truly extraordinary enlightenment and determination.”

—Daisaku Ikeda, Buddhism: The First Millennium, p. 127

The Early Transmission of the Lotus Sutra

“After the [Buddha] has entered extinction we will travel here and there, back and forth through the worlds in the ten directions so as to enable living beings to copy this sutra, to receive, embrace, read, and recite it, understand and preach its principles, practice it in accordance with the Law, and properly keep it in their thoughts.”

—The Lotus Sutra and Its Opening and Closing Sutras, p. 232

Early Buddhist Timeline:

• c. 500 BCE, Shakyamuni—Birth of Buddhism

• c. 268–232 BCE, King Ashoka—Buddhism spreads throughout India

• c. 155–130 BCE, Greek King Milinda and Buddhist monk Nagasena—Dialogues between East and West

• 1st century BCE to 2nd century CE, Lotus Sutra—Birth of Buddhist scriptures

• c.127–155, King Kanishka—Buddhism reaches Central Asia

• c.150–250, Nagarjuna—Prominent Buddhist scholar, India

• 4th century, Vasubandhu—Prominent Buddhist scholar, Pakistan

• c. 344–413, Kumarajiva—Definitive Chinese translations of the Lotus and other sutras

• 538–597, T’ien-t’ai—Systematizing the philosophy of the Lotus Sutra

• 711–782, Miao-lo—Maintaining the Lotus Sutra’s prominence

• 753—T’ien-t’ai’s teachings reach Japan

• 767–822, Dengyo—Tendai school established in Japan

• 1222–1282, Nichiren—Practice established for all people to attain Buddhahood

A Religion for All Humankind

“The Buddhism of Shakyamuni was destined not simply to remain a religion of the Indian people alone. Rather, it possessed characteristics of universal appeal that permitted it to transcend national and racial boundaries and present itself as a religion for all humankind.”

—Daisaku Ikeda, The Flower of Chinese Buddhism, p. 1

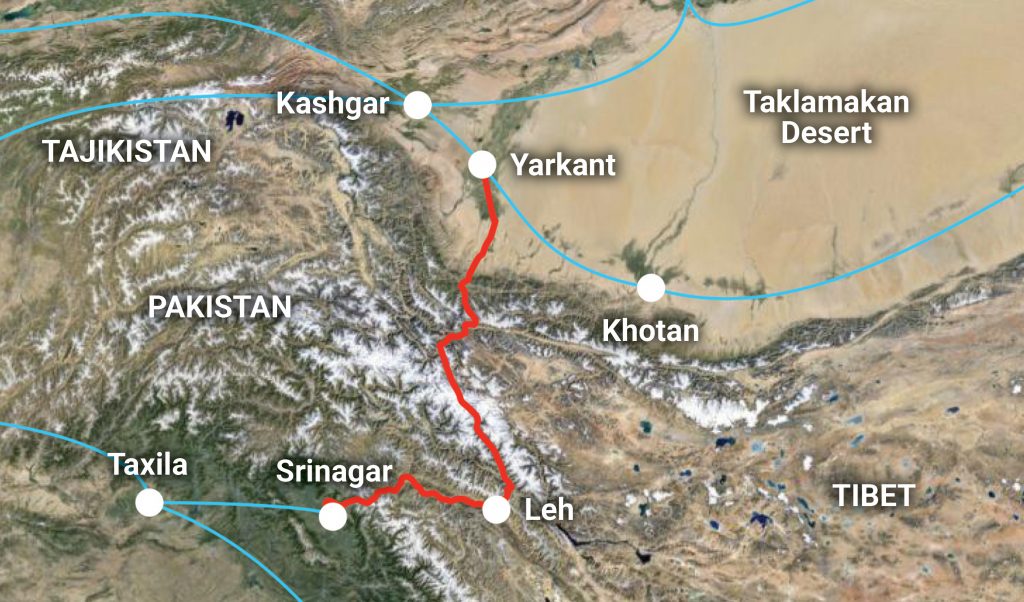

The Dras River in northern India was one of India’s main links to the Silk Road through the Karakoram Pass. Through valleys, gorges, foot trails and paths—trade and commerce, ideas and culture, the teachings of Buddhism and the Lotus Sutra—all found their way to China and beyond.

“The Silk Road Crossed by Marco Polo”

Detail of a 14th century map depicting Marco Polo’s journey to northern China.

Tang Dynasty Horse (replica)

The horse is representative of Chinese expansion, which secured the trade routes that gave rise to the Silk Road. This network of trade routes further expanded and enabled the exchange of goods, culture and ideas between China, Central Asia, India and Persia.

This horse with sancai or “three-color” glaze is representative of Chinese Tang dynasty sculpture. The sancai glaze, originating from Central Asia and used by Chinese sculptors, shows the cultural exchange along the Silk Road.

Tang Dynasty Camel (replica)

“The camel, known as the ‘ship of the desert,’ was one of the principal means for traveling that road. Chang Shuhong, the late honorary director of China’s Dunhuang Relics Research Institute, observed that the hoofprints of camels resemble lotus flowers.”—Daisaku Ikeda

Traders on the Silk Road often used camels to carry their goods because the animals could travel a long distance without water. Camels, symbols of prosperity, were one of the favorite subjects of Chinese craftsmen in the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE).

Taklamakan Desert

“[Buddhist missionaries] determined to carry the teachings of their faith to the people of other lands … [and] were prepared to face [all manner of] danger and hardship in the pursuit of their goal.”

—Daisaku Ikeda, The Flower of Chinese Buddhism, p. 21

Buddhists risked their lives crossing the treacherous Taklamakan Desert, said to mean “Desert of Death” or “Place of No Return.” They made the difficult journey both to seek and to transmit the teachings. Crossing the desert could take months, not including rest stops along the way. In time, Buddhism thrived in the oasis towns scattered along the rim of the desert, where the oldest manuscripts of the Lotus Sutra were found.

The Taklamakan is one of the largest sandy deserts in the world (600 miles across, 260 miles wide) in the northwest region of modern China, where temperatures range from 4ºF to 100ºF. It is one of the most inhospitable places on the planet, with high winds and frequent sand storms. Until sea routes were established, crossing the Taklamakan was the only connection between the East and the West.

Kumarajiva: Transmitting Buddhism to China

“It was the translations of the famed scholar Kumarajiva that communicated the essence of Buddhism to China with unmatched precision.”

—Daisaku Ikeda, September 2001, Living Buddhism, p. 32

Kumarajiva (c. 344–413) is known for his unequaled translations of Buddhist texts. Born in Kucha, a small state along the northern rim of the Taklamakan desert, he traveled throughout Central Asia and India, where he mastered several languages and the Theravada and Mahayana traditions of Buddhism.

Kumarajiva had longed to translate the Lotus Sutra ever since his teacher gave him a copy of the text, saying: “The sun of the Buddha has set in the west, but its lingering rays shine over the northeast. This text is destined for the northeast. You must make certain that it is transmitted there.”

The emperor of Northern China summoned Kumarajiva to his court. Along the way, the emperor was overthrown and Kumarajiva was held in captivity for 16 years. The new emperor eventually freed him from captivity, brought him to the capital in Xian and gave him the title “Teacher of the Nation.” Kumarajiva translated 294 volumes of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese, including his enduring translation of the Lotus Sutra.