Living Buddhism: Hello, Phyllis. We understand that you’re an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter and have played a key role in expanding SGI-USA’s Peace Hands Group, often by introducing fellow interpreters to the practice. What has fueled your passion to share Buddhism with others?

Phyllis Sapp: That’s right. Becoming a part of the Peace Hands Group, composed of ASL interpreters, has been at once one of my greatest joys and hardest-fought journeys.

To your question, when I began my practice, I was someone whose happiness and self-worth were tied up entirely in what others said and thought of me. When praised, I was elated; when disparaged, crushed. This was the case in all my relationships with friends, partners, co-workers and bosses. And challenges with finances, family and health completely swayed me. I was “happy” when my external circumstances were problem free and devastated when problems arose, dragged about by my environment. Practicing Buddhism, however, I’ve come to enjoy a much more stable and joyful state of life, even when problems arise. Appreciation and sheer joy are what propel me to share this incredible practice.

When did you begin chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo?

Phyllis: I began chanting in the summer of 1986 and received the Gohonzon that winter. From the jump, I was a strong chanter and loved being around SGI members, but my study wasn’t very strong. However, just by showing up at meetings, I deepened my study, because that’s what everyone around me was doing. I remember encountering the book from Ikeda Sensei Learning from the Gosho: The Eternal Teachings of Nichiren Daishonin. The very last lecture was on the writing “Happiness in This World,” and the closing sentence of the first paragraph completely hooked me. Sensei says, “When we deeply understand this Gosho, we have internalized the secret of faith and of life” (p. 233).

Well, who doesn’t want to know the secret of faith and life? Reading Sensei’s words, I thought: This is great! If I just deeply understand this one Gosho, I’ll have unlocked the secret of faith and life! At a glance, I thought, How hard could this be? But you should see my copy of this lecture, its margins marked up and down, its pages worn thin. Over the years, I’ve read it close to a hundred times. I’ll quote a piece of it here:

It is the mind of faith, which is invisible, that moves everything with enormous power and strength in the best possible direction—toward happiness, toward the fulfillment of all our wishes.

Someone who puts this principle into practice is a Buddha of absolute freedom … who, while remaining an ordinary person, freely receives and uses limitless joy derived from the Law. (p. 239)

Chanting with this conviction has awakened my “mind of faith.”

You first began learning ASL in your late 40s. What compelled you to take on such a challenge?

Phyllis: Even now, it surprises me sometimes. For the longest time, my life revolved around my sons, Austin and Alex. The jobs I chose to work were ones that allowed me to be flexible around their schedules. In short, I was a mother and that was my thing. But one day, when they were in middle school, my husband made a prescient comment that made me think. He said, “You know, you might want to draw up a new bucket list—it won’t be long before your goals and dreams will be moving out the house.” Knowing how fully I’d invested myself in raising the kids, he wanted me to bear in mind a future for myself after they’d left the nest. He’s right, I thought. Where would I carry out my mission when they did? This was the question I took with me to the Mentor and Disciple Conference at the Florida Nature and Culture Center in 2008.

It sounds like you found an answer there. What happened?

Phyllis: We were all gathered and given choral sheets to a song I’d never sung before. For whatever reason, I wasn’t interested in singing this unfamiliar tune. In fact, I was feeling negative about it. I’d shuffled my way to the back of the group, planning to hide there and bluff my way through, when this young man beside me asked if I could track the lyrics on the music sheet with my finger.

“No,” I said. “Actually, I’m sitting this one out.”

“Oh, all right” he said. “But the thing is, I’m hard of hearing. I can’t follow along by listening, but if you follow the lyrics with your finger, I can sing, too.”

His words shook me like a thunderbolt. Here was someone wanting to give his all to a song I was shrinking from, who had actively sought out support I could easily lend but, due to my own negativity, had denied. His proactive, seeking spirit was like a light flooding my life, revealing to me the negativity and avoidance hiding there.

As we sang, my finger bobbing beneath the words, I felt a strong sense of mission. Maybe this is something I can do, a kind of help I can give. Later on in the conference, I followed the quick, intelligent hands of the ASL interpreters accompanying the presentations. I was a district women’s leader at the time, and I thought to myself: How many deaf and hard of hearing people are there in Minnesota who would like to practice Nichiren Buddhism? How many are unable due to a lack of interpreters? Leaving that conference, I reported cheerfully in my heart to my mentor: Sensei! Don’t worry about the deaf and hard of hearing in Minnesota! I’m going to become an ASL interpreter, making sure that anyone who wants to can participate in our kosen-rufu movement!

I was absolutely sincere, but gosh, so naive! I had no idea how daunting a challenge it would be to begin training as an ASL interpreter in my late 40s! Of course, it didn’t take long for me to figure out that learning to sign was a far more intensive endeavor than tracking lyrics with a finger. In fact, it would require me to do something no one in my family ever had: attend and graduate from college. Ages ago, I’d barely graduated from high school. As soon as I realized that college was involved, I thought, Oops, never mind! I guess I was a little hasty with that promise, Sensei! I dropped the idea and forgot about the whole thing.

But not for long. What brought it back to mind?

Phyllis: I’m not sure what exactly caused the memory of this promise to come surging forth from my life, but it did, two years later at an SGI study conference. I can’t say why, but I felt myself weighed down by this intense negativity that wouldn’t let up. I was eating a snack outside during a break in the conference when I felt this wave of anguish crash over me—I remembered the determination I had made to learn ASL.

A senior in faith assured me that no matter how many times we fall down, the important thing is to get back up and keep fighting. So long as I continued to chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo with a vow for kosen-rufu, there was nothing I could not accomplish.

I felt my negativity getting bust up like heavy clouds by sunshine. When I came back to Minnesota, I enrolled in community college to study ASL. I decided that I would fulfill my promise to Sensei no matter what. Of course, when we make a vow for kosen-rufu, obstacles invariably arise.

One week into the first semester of school, my husband lost his job. Suddenly, I needed to take on work to pick up the slack—I found a job at a grocery store thinking, I’ll be here six months—six months tops. I was there for five years, which is also how long it took me to earn my two-year degree.

What was that like?

Phyllis: Well, I was working, raising kids and supporting SGI activities as the region women’s leader all while going to school—it was nuts. But because it was nuts, I learned what it means to base my life on daimoku and a vow for kosen-rufu. While there, the grocery store ran on a skeleton crew and a shoestring budget, so the workload was intense. At school, too, the work was overwhelming. As mentioned, most people training to become ASL interpreters have signed from a young age, usually to support a family member. I was starting from scratch, way behind everyone in all of my classes. There were days I thought I would drop out, but then I’d remember my vow and return to this passage from Sensei’s lecture on “Happiness in This World,” where he explains that the mind of faith moves our life in the best possible direction.

Whenever I felt deadlocked, I returned to the spirit of this passage and, chanting to fulfill my vow for kosen-rufu, felt joy rise up from within my life at the understanding that I was in the place of my mission.

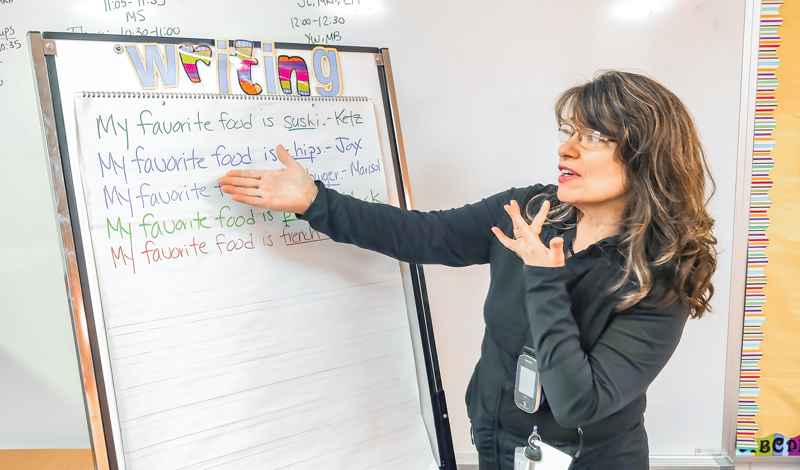

When the opportunity arose, I naturally shared Buddhism with those around me, at the grocery store and at school. At my work, five people began their practice and received the Gohonzon, while at school, fellow students as well as my instructor, a top notch interpreter, took up their practice and began supporting as members of the Peace Hands Group, having experienced actual proof of the transformative power of the practice in their own lives.

That’s incredible! What would you say to those who are intimidated by the prospect of school?

Phyllis: First, I’d say to everyone earnestly practicing this Buddhism: You are amazing—just as amazing as someone with a bunch of diplomas or a Ph.D. Also, if you’d like to go to school, you absolutely can! Looking back at getting my ASL degree, I think to myself: I did it! I really did it! It was so hard, but now, whether signing with children at work, or for our precious SGI members, or exchanging stories of profound human revolution with fellow interpreters, I feel like my heart is about to burst with joy and know this must be, as Nichiren describes, the “boundless joy of the Law” (“Happiness in This World,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 681).

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles