Living Buddhism: Earlier this year, you received your associate’s degree in Behavioral Sciences from Pasadena City College and are now on track for a bachelor’s in Africana Studies from California State University, Northridge. These accomplishments are some 50 years in the making. Certainly, you followed your own path to higher education.

Stephanie Wilson: Well, I’ve always been something of an oddball. An only child, raised by my aunt and uncle, I may have made my own way more than my friends who came up in typical two-parent households. Maybe because my family did not look “normal,” I was inclined to question things that others seemed to accept as normal.

What kinds of things did you question?

Stephanie: Church, for instance. Mine was an all-Black church, a lively place and, for me at that time, a good place to be. But while everyone was singing and giving praise, my mind was racing. Just across the street was an all-Asian church. What did they believe? I wanted to know. How did they worship? Why did we worship separately? I’d ask around but no one seemed interested.

At school I had the same problem, firing off questions about things the other kids didn’t seem to put stock in. It was really my love of learning that got me pegged as an oddball. I was teased for liking school too much, bullied, even. So, over time, I learned to keep my questions to myself. I didn’t have the confidence to embrace what was a little odd, a little different, about me—my restless seeking spirit.

There was one class, though, where you didn’t hold back.

Stephanie: That’s right. In 1968, I attended Los Angeles Valley College as a freshman and enrolled in a course on African American history. I aced it; I let loose. The history of Black people—not just as a few tragic footnotes in U.S. history but as a collection of voices and stories of real people, Black people, who had struggled and survived that history—presented to me a legacy of spiritual strength and moral courage that I had never encountered in a classroom. It made me more curious about African American history and culture, and by extension, more curious about myself and my community. That class confirmed for me my sense that ordinary people possess deep inner strength and wisdom. I was guided by the question, What inner strength and wisdom was within my own life and the life of my community?

What a profound question. How did you see yourself using a college education?

Stephanie: I had always known that I had a deep spirit in me, only that it wasn’t moved so much by the notion of God as it was by acts of service to others. I remember when I was 14, too young myself to register folks to vote, running all over Oakland with a lady from the church to register volunteers who were themselves of age to do that. Though young, I felt powerfully driven to put power into the hands of ordinary people, to empower them to look within themselves to come up with their own answers to what was going on in their communities and personal lives. When I enrolled in college, it was because I wanted to receive an education that would help me do this for the people in my community.

But, a few big things caused me to drop out. My uncle, my father figure, had been battling cancer for some years and passed away, a loss I took very hard. I also worked full time and stepped up at home to support my aunt. Then, my second semester of freshman year, I became pregnant with my daughter. But something very important had taken place while at college—a classmate introduced me to Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. Though I did not attend Buddhist meetings or fully grasp the meaning, I would chant when I was stressed. It was not until I enrolled in college again years later, at Los Angeles Trade-Technical College in 1986, that this seed would sprout, and I’d engage with Buddhism in earnest.

What spurred you to fully engage the practice after so many years?

Stephanie: Well, a whole lot of things. I was 36 and a mother of two; my son had been born in 1974 and was 12. My daughter was 17. I was working a swing shift as an indoor technician for Pacific Bell while attending classes at L.A. Trade-Tech to get a better paying job. My aunt and I had moved to a new neighborhood, but not a very safe one for raising children. This was the ’80s, at the height of the crack epidemic in Los Angeles, and I worried constantly about my children.

I was near the same age as some of my Trade-Tech teachers and connected with them as peers. I asked one teacher who was battling cancer how she kept her spirits up, and she said it was by chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo.

“I don’t have any money!” I blurted. “Can it help with that?”

You could say that I started practicing Buddhism out of emergency.

What made you want to keep practicing?

Stephanie: The people and the diversity. I went to that first meeting, and it just felt good, it felt right. People really cared about what I was going through; they wanted to know what was going on and to support me. Chanting for a better job and a supportive family environment, I put faith first and soon found that, despite my crazy schedule, everything was falling into a productive rhythm.

In the mornings, I made dinner and put it in the fridge for the kids to come home to. By 9 a.m., I would’ve dropped them off at school. My own classes were 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., after which I left for my swing shift at Pacific Bell, near campus. I’d get home around midnight and sit down in front of the Gohonzon for gongyo. Despite this, I rarely missed an SGI district meeting. My prayer for a supportive family was answered by the SGI community itself; knowing my hectic schedule, members and leaders would drive from all over to chant at my house, to give guidance and encouragement.

I’ve always been inspired by Ikeda Sensei’s words: “Reality is harsh. It can be cruel and ugly. Yet no matter how much we grieve over our environment and circumstances nothing will change. What is important is not to be defeated, to forge ahead bravely. If we do this, a path will open before us” (daisakuikeda.org). I found this spirit alive in the members of my SGI family, who made me feel that I could do anything I set my mind to.

Soon I secured work that I enjoyed for the next 10 years as the director of public relations and recruitment for a youth mentoring program. What’s more, though I had not yet received a college degree, I was elected to manage a team of people who had. I was beginning to come to terms with what I had to offer, as someone who did not hesitate to question and collaborate with others to find answers to problems as they arose.

That’s wonderful. How did you go about pursuing your degree?

Stephanie: Well, there was always not enough time or not enough money. But still I wanted to go. As much an odd ball as ever, I still had many questions about the world I wanted answers to. I was finally ready to enroll again in 2004 but was appointed legal guardian of my three grandchildren. So the dream was put on hold once more. But by this time, I had developed what I call my Buddha muscle—the conviction that everything happens for a reason. There was no doubt in my mind that my grandchildren and I had chosen to walk the path of life together. For the past 18 years, we have done our human revolution side by side.

I like to say that they have done for my Buddha nature what hot oil will do for a kernel of popcorn. Without them, I wouldn’t have “popped” into the strong, happy person I am today.

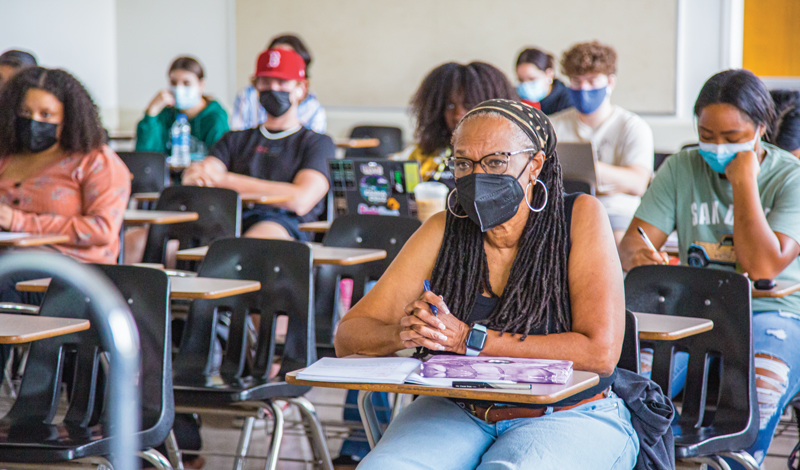

Working fulltime while raising grandchildren, you managed to return to college in 2020.

Stephanie: Yes. For the past 16 years, I’ve worked in home service, assisting underserved communities with their daily needs. What I’ve found is that ordinary people possess rich wisdom and insight. However, you wouldn’t know this by opening any magazine or newspaper sold in this country. But I know better. When Sensei directs us toward the Gohonzon, he is encouraging us to pull forth from within our own lives the answers to life’s problems. In the SGI, it seems that someone is always telling me, warmly, firmly, on Sensei’s behalf: “Please believe in yourself! Whatever the obstacle, you can find a way!”

Even at my age, I wanted to pursue an education that would give me the skills to write with and for the people in my community, to draw attention to the everyday struggles and diverse perspectives of ordinary people, and empower them to take action to remedy the problems they see in society.

When you received your associate’s degree from Pasadena City College in May, we understand that you also gave a commencement address. What did you say?

Stephanie: Buddhism is about appreciation. I submitted my speech for commencement because I wanted to appreciate my teachers who believed in and helped me along the way. I also wanted everyone listening to know that it is never too late to accomplish a dream. Actually, an older gentleman came up to my family after the ceremony to say that my speech had inspired him to go back to school. “Thank you,” he said. “Now I know that this is something I need to do.”

What’s next?

Stephanie: This year, I turn 72. My prayer is one of deep appreciation; I’ve lived a long, wonderful life and want to live a lot longer! I want to contribute to society in my own unique way based on the time I’ve spent on earth and the experiences I’ve had as a mother, grandmother and great-grandmother; as a public servant and student; as a disciple of Ikeda Sensei. Through my own example, I want to inspire people from all walks to dig deep within their own lives to discover their own answers—to realize that they, too, have something to say.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles