Living Buddhism: Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us. For the past 16 years, you’ve taught science to middle schoolers. We understand you were recently named one of five 2022 California Teachers of the Year. Congratulations! What has shaped you as a person and teacher?

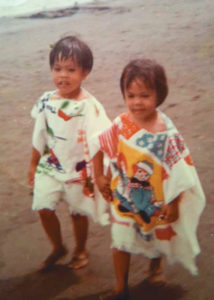

Photo courtesy of Nichi Aviña

Nichi Aviña: Thank you so much. In 2001, my brother, Nico, unexpectedly took his own life at 27 years old. I will never forget my father’s wail at 3 a.m., finding him in the stairway. The winter that fell over our house was truly bitter. In the weeks and months that followed, I sometimes wondered how spring would ever return.

I had my Buddhist practice, so I knew that there was no other choice but to transform my pain and suffering into something of value, not just for myself or my family but for all of society.

How did you find a way forward?

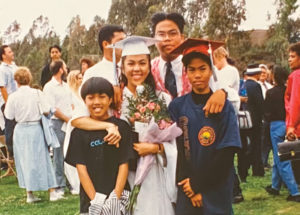

Photo courtesy of Nichi Aviña

Nichi: At the heart of Buddhism is the bond of mentor and disciple. Vital to me at this time was having a mentor in Ikeda Sensei. I etched in my heart the words Sensei sent us shortly after Nico’s passing. He encouraged us that though this must be a very difficult time for us, with strong faith, we could become happy and that happiness would extend to him.

It was with this resolve—to lead a life of joy on Nico’s behalf—that I threw myself into SGI activities. I knew that doing my best to encourage one young woman after another to develop without limits, fulfill her mission and do her human revolution for the betterment of society would help me find a deeper joy myself.

What was the process like for you?

Nichi: The pain was still there. One day, my women’s leader assured me that the causes I was making for kosen-rufu were precisely the causes that would guarantee my victory. I took her words to heart, and continued to fight to urge other young women to stand up in faith and become absolutely happy.

What resulted from those efforts?

Photo courtesy of Nichi Aviña

Nichi: In 2002, I was struck when I read Sensei’s encouragement about how attaining enlightenment begins with making a vow. I had already determined to change the poison of my brother’s suicide into medicine. But how, concretely, would I do that? What was my vow? I prayed long and deep to understand my life’s mission as a Bodhisattva of the Earth, and a vision came to me—of me helping children perceive their lives as great treasure towers. The “Treasure Tower” chapter of the Lotus Sutra describes the emergence of such a tower—an allegory for the infinite dignity within the life of each person. I decided that my mission was to teach children that their lives were worthy and deserving of the ultimate respect.

A founding principle of Soka education is to treasure the life of each child.

Nichi: Exactly. I had to become a Soka educator; I had to teach children that their lives themselves are treasure towers. I went back to school to get my masters in education and landed a job in 2005 as a middle school science teacher. That job had special significance as it was in middle school when Nico began using drugs.

Looking back, his drug use was a way of coping with the effects of earlier traumas that he and I encountered as children: poverty, sexual abuse and a difficult move at a young age from our home country of the Philippines to San Diego. Our loving parents, Dina and Abe Ellorin, worked hard each day, but this could not protect us from the racial discrimination we felt growing up poor and never quite fitting in America.

How did these experiences inform your approach to teaching?

Photo courtesy of Nichi Aviña

Nichi: In the 16 years since I began teaching, I have encountered many students. Always, I have had a soft spot in my heart for those troubled, hard-to-reach students. One of the greatest rewards as a teacher is to see your students’ lives blossom—students who might not have thrived had you not been there to assist them through their most difficult, heart-wrenching moments.

Tsunesaburo Makiguchi said of students: “Even though they may be covered with dust or dirt, the brilliant light of life shines from their soiled clothes. Why does no one try to see this? The teacher is all that stands between them and the cruel discrimination of society.”[1] As a teacher and a Buddhist, I feel it is my mission to go to the margins of society and bring every student into the fold of community. It is often in heart-wrenching moments with the most troubled students that I find I can most clearly share and demonstrate the life-affirming principles of the Lotus Sutra and the message of Soka education.

Do any students come to mind?

Nichi: One student was a first-generation U.S. immigrant, like me. Her father had fallen severely ill, and she was acting out at school. After an incident, she was sent to the principal’s office. There, she asked for me. When they called me in, I saw the sadness in her eyes. I sat with her, without judgement, until she was able to communicate. I listened. I understood she was at a pivotal moment in her life and that this conversation would influence the trajectory of her life. I explained to her the principle of cause and effect. All the causes we make, I said, have an effect. Though we may not see the effects right away, our causes, good or bad, are stored within our lives and bear fruit when the time is right. I could tell that she got it.

We stayed in touch over the years. Though it was not an easy road, this young woman overcame many obstacles and is now a successful electrical engineering student in college. She even encountered the SGI on her own after high school and, knowing that I am a member, started chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo and joined the SGI.

What a moving story. How has your life developed over the past 16 years?

Nichi: I have had many ups and downs. My first marriage ended badly, and around the same time I lost my job due to budget cuts. But I pressed forward, bearing in mind the words of Nichiren Daishonin: “Suffer what there is to suffer, enjoy what there is to enjoy. Regard both suffering and joy as facts of life, and continue chanting Nammyoho- renge-kyo, no matter what happens.”[2]

In 2012, at age 37, I found love again and remarried. We started a family, and I began teaching again. Through all of this, I kept my Buddhist practice at the center of my life. When asked to become a district women’s leader in my new home of Palm Desert, I said yes, even though I was working full time and raising three young children.

Striving alongside the women of Palm Desert reminded me of all the potential I had unlocked by putting myself, as a young woman, in the mainstream of the SGI movement. Through mutual encouragement and support, we in Palm Desert invigorated and empowered one another to establish a courageous personal practice translating into concrete breakthroughs in our everyday lives.

The teachers at Palm Springs Unified School District, where I work, were masters of their craft. But I felt I brought to the table a capacity and drive to bring people from all walks of life together around a shared vision. This capacity was especially honed in my years following my brother’s death. Soon, the school and local community came together around one project after another. Parents, teachers, students and community members of various professional backgrounds all pooled their talents and resources around a host of initiatives, beginning with a school garden. I went on to jumpstart a trauma-responsive teacher workshop, and multicultural literacy and art mentoring programs.

This past year, in which we wrote and received a grant to bring in a local artist, was particularly significant for me. Nico had been a talented artist but without a mentor or a space to develop himself.

We understand that during the pandemic, far from slowing down, your career soared to new heights.

Photo courtesy of Nichi Aviña

Nichi: Yes. Even in the new stresses that came with a digital environment, I found that it was possible to give a sense of agency to the kids—to give them center stage, make meaningful connections with one another and have lots of fun.

Whatever you are teaching, however you are teaching it, you are, at the deepest level, teaching who you are. Keeping my Buddhist practice and my mentor at the center of my life, I am always reminded that mine is a winning life. I teach the kids that they can win in my class and that they can use what they have learned in other parts of their lives and win there, too. I think this is why, in February, I became Cielo Vista Charter School’s Teacher of the Year; in April, Palm Springs Unified Teacher of the Year; in May, Riverside County Teacher of the Year; and in September, I was considered for California Teacher of the Year.

Around the time of this last nomination, I was asked to become the chapter women’s leader for Palm Valley Chapter. That week, I wrote to Sensei, telling him about the nomination, to which he responded that he would be praying for my success. I accepted chapter leadership and, a week later, was notified by the state superintendent of public instruction that I was one of five California teachers of the year. I have since had two days named in my honor. October 26, 2021, was Nichi Aviña Day in San Diego; and on November 18, 2021, the 91st anniversary of Soka Gakkai Founding Day, the Palm Springs City Council announced Nichi Aviña Day.

Congratulations! What are your future goals?

Nichi: Next year, I will be asked to speak at several panels across the state and was even offered to teach a class to new teachers at California State University, San Bernardino. I am currently working on a roadshow to present to teachers across the state. It will showcase the principles of Soka education, how to treasure each child, especially the most difficult and traumatized students—the Nicos of this world. I have also found in my research on trauma responsiveness that with just a few key practices, teachers and schools can turn the tide on the current mental health crisis afflicting our nation’s youth. This will be my mission as a sister, a Soka educator and a disciple of Sensei.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles